Meat 201 is an advanced examination of the four major cuts of beef that you’re likely to see at a steakhouse. The four major cuts are Filet Mignon, Strip Steak, Porterhouse and Rib Eye. For more general information about these cuts, and for information about other cuts of beef, please see my MEAT 101 and MEAT 102 posts.

1. Porterhouse

Etymology: There is some difference of opinion on the origin of the word “Porterhouse,” with several restaurants and cities claiming to have created the name. For example, Martin Morrison served large T-bones in his Pearl Street (Manhattan) “Porter House” around 1814. This history was popular in the late 1800’s, but some say a Cambridge, Massachusetts proprietor by the name of Zachariah B. Porter added his name to the steak. Still, others argue that the Porterhouse name stems from various 19th Century U.S. hotels or restaurants called Porter House, such as the Porter House Hotel in Flowery Branch, Georgia.

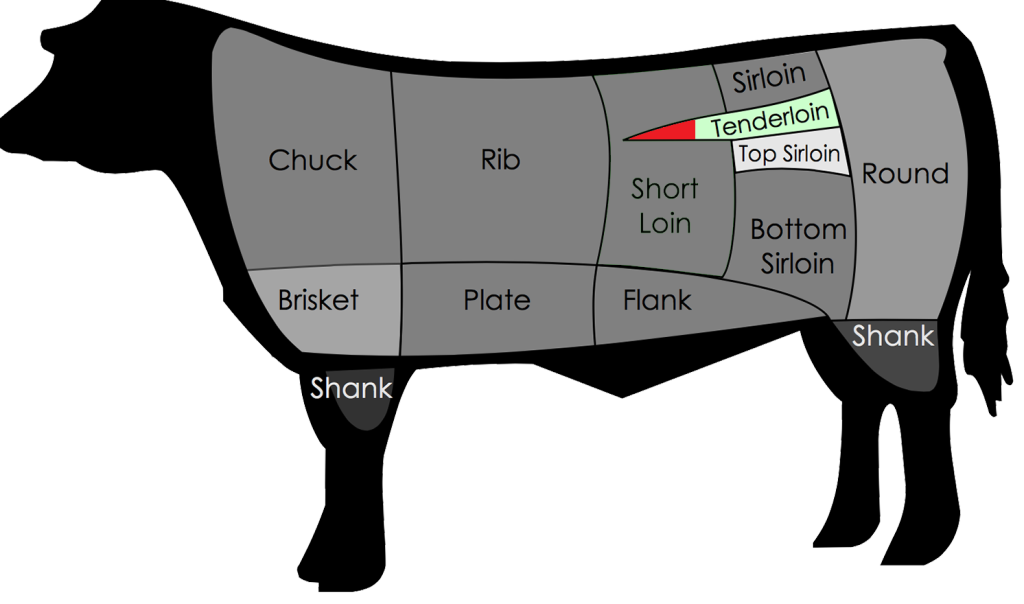

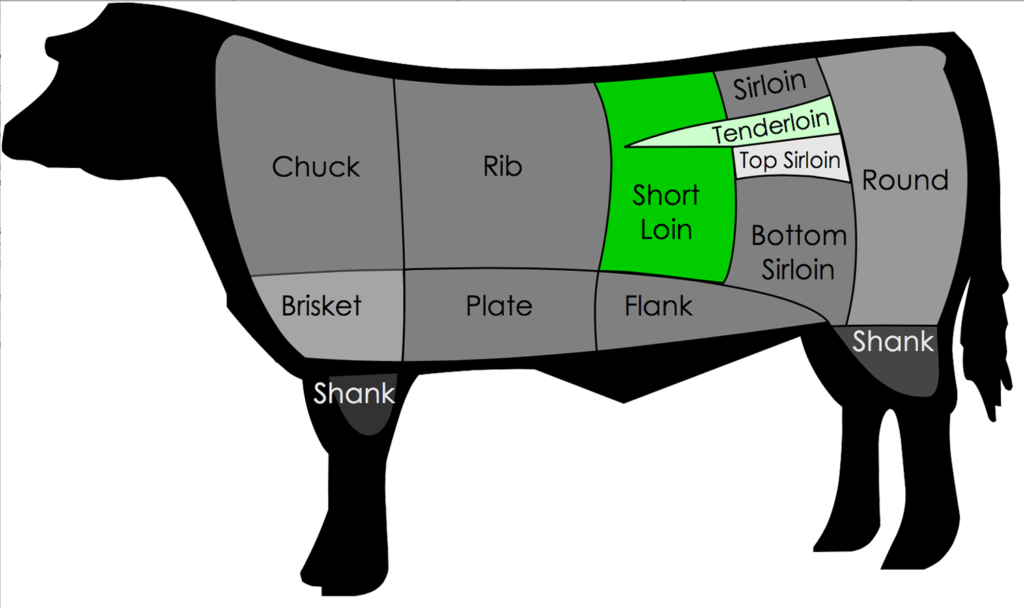

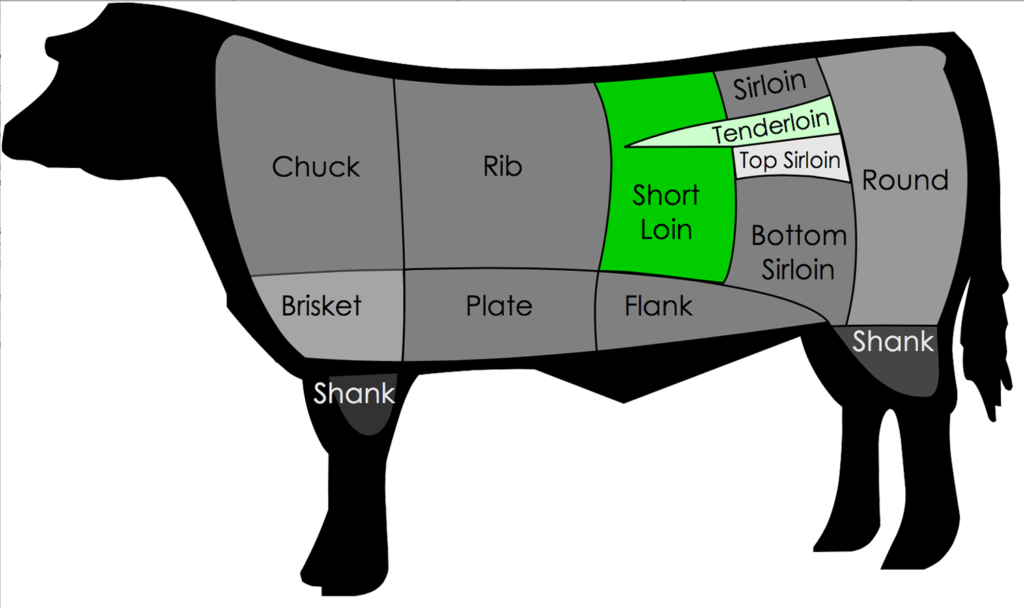

Anatomy: The Porterhouse is a cut of steak from the short loin portion of the animal that contains both strip loin and tenderloin meats. See the highlighted portion in the diagram below:

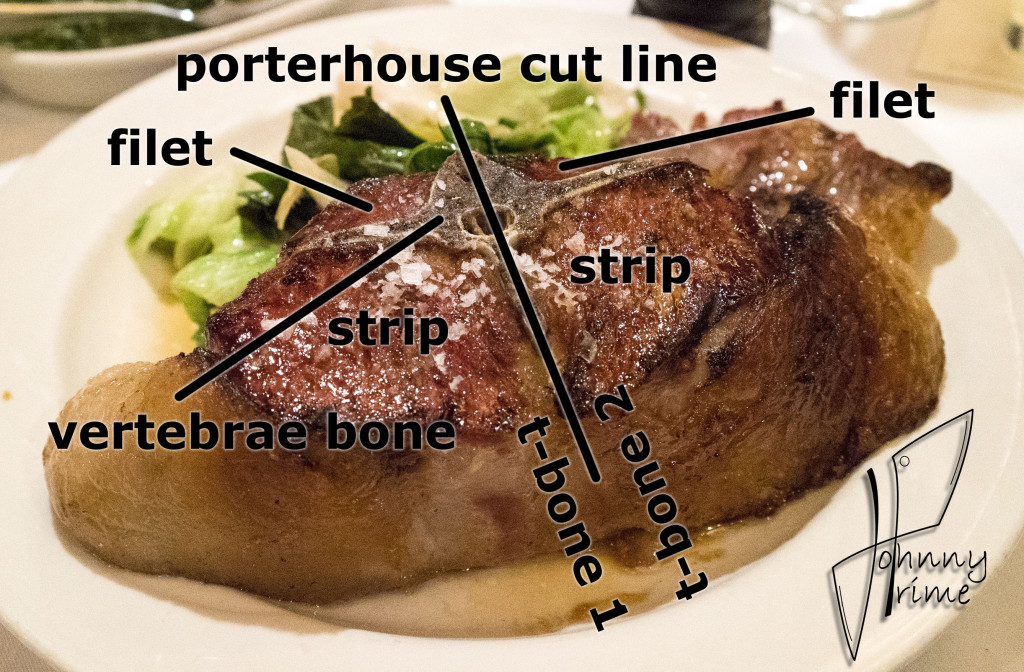

It is cut from a lumbar vertebra that is sawed in half through the vertebral column.

The downward prong of the “T” is a transverse process of the vertebra, and the flesh that surrounds it (spinal muscles) makes up the meat of the Porterhouse.

Essentially, it is a large T-bone steak from the rear of the animal that has two different types of meat (tenderloin and strip loin), one on either side of the “T.” In the picture below, the strip loin or Strip Steak is on the right, and the tenderloin or Filet Mignon is on the left.

The small semicircle at the top of the ‘T’ is half of the vertebral foramen, which is the name of the hole that passes through each vertebra for housing and protecting the spinal cord. They run the whole way up the back, all the way up to the brain of the animal.

The anatomy of a Porterhouse differs from that of a T-bone only in that the Porterhouse contains a larger portion of tenderloin than its T-bone counterpart.

This is primarily due to the fact that Porterhouse steaks are cut from further in the rear of the animal, from lumbar vertebrae, where the tenderloin is much thicker. Experts differ, however, on how large the tenderloin must be to differentiate a Porterhouse from a T-bone. The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Institutional Meat Purchase Specifications state that the tenderloin of a Porterhouse must be at least 1.25 inches thick at its widest, while that of a T-bone must be at least 0.5 inches.

Here is a shot of a short loin with multiple vertebrae still intact and not portioned out into individual Porterhouses and T-bones.

You can see on the left there is a good sized, thick portion of tenderloin. That thins down as you move the the right, and seems to disappear by time your eyes reach the far end of the cut.

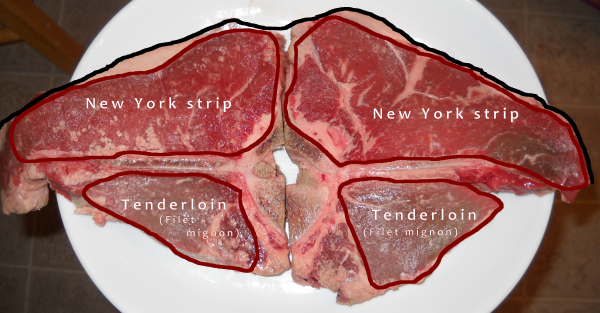

Just to drive home the anatomy a little more, here is a great excerpt and image from Russ Cooks:

“Up close and personal, this is where the T-bone fits.

The black line across the top of the two T-bones pictured here is the outside (top of the back) of the steer. You can see the T-bone in the schematic illustration higher up on this page as the topmost part labelled Rib. Above the ribs, what you touch if you pat the steer’s back, is the New York strip. Beneath the ribs is the tenderloin from which a filet mignon is often cut. T-bone steaks cut closer to the shoulder are known as Porterhouse while those cut closer to the loin are just T-bones.”

Preparation: Most times, T-bones and Porterhouses are either grilled, seared in a pan, broiled or blasted with high heat in specialty steak ovens made for charring the outside of the meat without over-cooking the inside. Butter is essential, and heavy seasoning is important as well. Herbs and garlic help boost the flavor too.

Flavor: Since this cut contains both the Filet Mignon and the Strip Steak, I refer you to the flavor sections for those cuts below, with a notation that the bone being left in often adds a more robust flavor while helping to retain tenderness and juiciness. These are very popular items at steakhouses because they can be cut large enough to feed anywhere from two to four people. Additionally, with two different types of meat in one steak, one can vary the flavors that one experiences with each bite.

2. Filet Mignon

Etymology: Filet, in culinary terminology, means boneless. Mignon, in French, means dainty or small. As such, this is a steak ideally suited for chicks: small/dainty, and with no bone.

Occasionally on a steakhouse menu you will see a “bone-in filet.” Given what I just mentioned above, that phraseology is completely self-defeating and confusing, as it simultaneously means both “bone-in” and “boneless.” However, it seems this sort of language is becoming commonplace. If it were up to me, I would prefer “bone-in tenderloin” to be listed on menus instead. There is no wording conflict with that phrasing, and it is an accurate description of what is being presented. In other words: all Filet Mignon is tenderloin, but not all tenderloin is Filet Mignon.

Anatomy: Traditionally, a Filet Mignon was cut from the anterior end of the tenderloin. In the beef chart image below, you can see a portion of the tenderloin section highlighted in red.

That is where Filet Mignon was typically located, though most butchers label all steaks cut from the tenderloin as Filet Mignon (this allows for larger portions). The tenderloins run along both sides of the spine. They taper from thick, in the posterior of the animal, to thin in the front.

In their unbutchered form, they contain what’s called the “silver skin” still attached to the flesh. This is a thick connective tissue that is pretty much inedible. When butchering the full tenderloin, you will want to slice that off (it is NOT tender).

While this next photo is a repeat shot of a lamb vertebra Barnsley chop (the mutton chop from Keen’s), the anatomy is exactly the same for beef. This will illustrate exactly where the filet comes from. Essentially this is a double porterhouse, with a filet and a strip on each side. In addition to understanding the Filet Mignon, this image is useful in demonstrating the anatomy of the Strip and Porterhouse cuts as well, since they all come from the same place – the vertebrae of the animal:

Preparation: Preparations of this cut vary greatly. You may see this cut sliced thin and pounded flat, served raw for carpaccio. You may also see it finely chopped for tartare. A simple pan sear with butter and herbs, however, is probably the most common preparation.

Yet another style is Chateaubriand, which is a large section of the thick portion of the tenderloin that is roasted boneless, then sliced and served with a reduction sauce.

There is also Beef Wellington, which is a portion of tenderloin that has been coated with pate and then wrapped in puff pastry dough prior to cooking.

Flavor: Widely considered the most tender and least fatty cut of beef on the animal, the flavor should be uniform from one end to the other, with very tender and soft texture the whole way through. There is hardly any fat content in the standard cut of Filet Mignon. Some chefs will wrap the filet in caul fat (a lacy, fatty, web-like membrane that surrounds the stomach of an animal) before cooking. The webbing melts away during cooking and imparts a fat flavor into the meat. But it is more common to use things like butter, or to wrap a filet in bacon to add the fat flavor into the meat.

3. Strip Steak

Etymology: According to the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association, this steak is marketed under various names, including Ambassador Steak, Club Steak, Hotel-Style Steak, Veiny Steak, Kansas City Steak and New York Strip Steak. Delmonico’s offered Strip as a signature dish way back in the early 1800’s. Due to the cut’s association with NYC, the New York Strip Steak name was born.

Anatomy: The Strip is cut from the other side of the tenderloin, across the vertebra on the T-bone or Porterhouse.

Also known as strip loin, the Strip Steak is cut from the short loin part of the animal, from a muscle that does little work, like the Filet Mignon. It is generally more tender than the similarly situated but more posterior-located sirloin section of the animal. While it is essentially the same kind of meat as sirloin, the muscles in the rear do a bit more work than the short loin, so can be a bit more tough.

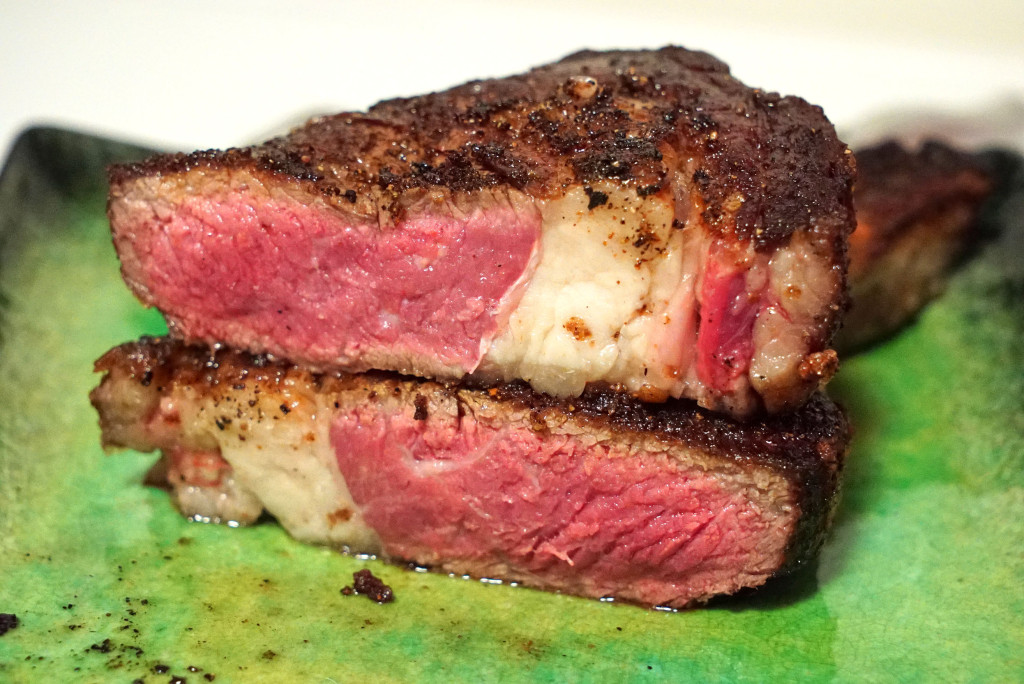

Preparation: For me, the Strip is best at medium rare, to preserve the tenderness and reduce any mealy or grainy textures that can develop from overcooking. It is always best to get a really great quality cut for this chop, something prime+, as all the intra-muscular fat, or marbling, will become soft and the muscle will tenderize all over. You will often see it marinated or rubbed with spices, to impart additional flavors, but grilling and broiling in the traditional style is fantastic as well, especially with butter and herbs. It can be served bone-in or boneless. Leaving the bone in will impart more flavor and help with the cooking process, since the bone conveys heat into the center of the meat while locking in juices. At home, marinade this puppy in something like soy sauce and garlic, and slap it on the BBQ for a few minutes on each side and you will have the perfect home-cooked steak.

Flavor: This cut contains fat in levels that are somewhat in between the tenderloin (virtually none) and the Rib Eye (plenty of good, melty fat). Like the tenderloin, there is little variation throughout the cut, so the flavors and textures are more uniform for the Strip Steak, unlike the Rib Eye which has varying textures and flavors from one end of the cut to the other. The texture of a Strip can sometimes be a little bit grainy or mealy, and a bit more tight than a Filet Mignon or a Rib Eye – especially if it’s cooked too much.

4. Rib Eye

I’ve saved the best for last. The Rib Eye is the most ultimate of steaks, period. It is an awesome cut of beef.

Etymology: The etymology on this is pretty self-explanatory. The “rib” part of the name is because this cut of meat is connected to a rib bone. The “eye” part of the name is a reference to the circular, more centrally located portion of the cut that is more uniform than the outer portions of the cut. You will likely see the Rib Eye steak, or rib chop, called by many names.

For example, the Cowboy Rib Eye is a bone-in version of the cut:

There’s also the Tomahawk Rib Eye, which is so named for its resemblance to a Tomahawk-style hatchet. When butchered, a long “handle” of rib is cut clean to expose the bone (it is “Frenched,” as they say), and the steak meat is left at the end of the handle to form the hatchet blade:

Here’s a shot of my buddy; he’s about to get clobbered with a Tomahawk Rib Eye by Chef Josh Capon at Bowery Meat Company:

There’s also the Delmonico cut, otherwise known as a Scotch Filet. Applying what you’ve learned here, you can probably guess that this cut is boneless (filet means “boneless” in French). Delmonico’s claims this cut as their own because they named a house special boneless cut Rib Eye steak after their restaurant, way back in the early 1800’s when they first opened.

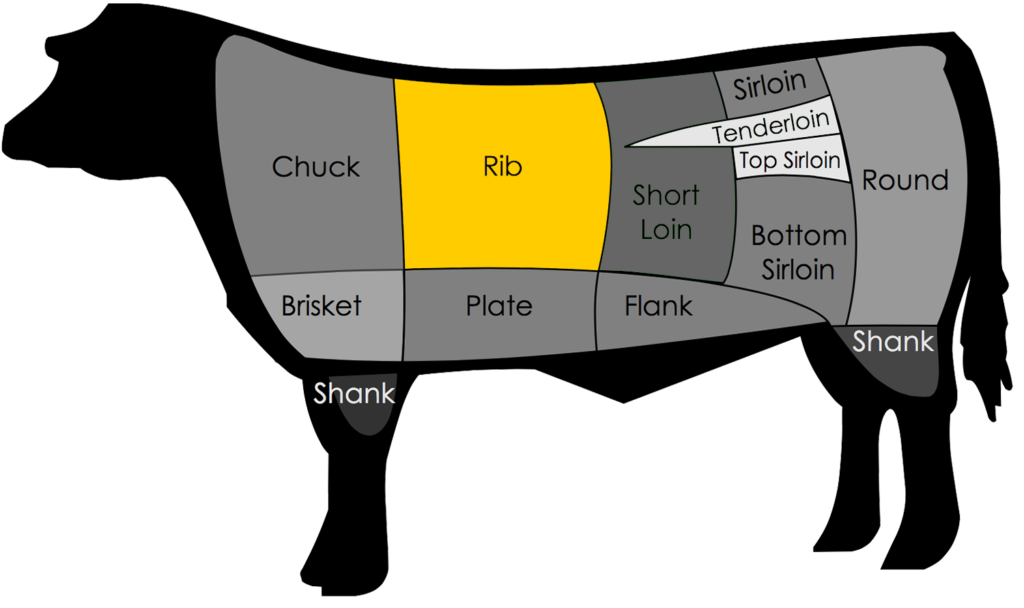

Anatomy: The rib section of beef spans from ribs six through twelve, and, obviously, hails from the rib section of the animal.

Rib Eye steaks are mainly composed of the Longissimus dorsi muscle (the “eye” portion of the steak) and the Spinalis dorsi muscle.

The more anterior your cut, the more Spinalis you’ll find in the steak. The Spinalis is the coveted cap of meat that wraps around the fatter end of the steak and usually has much more marbling than the rest of the Longissimus eye, or interior of the steak. That “fat cap” is also sometimes butchered away from the remaining eye.

Highly skilled butchers know how to remove it from its position across an entire standing rib roast section of ribs, so as to keep it all together as one giant cut. But then that ruins the rib chop, in my opinion, since you’re taking away the best part. Some steakhouses have taken to tying several Spinalis cuts together in a spiral formation to create an all-fat-cap steak. Bowery Meat Company has one such cut, which they call the Bowery Steak:

STK also offers one on special from time to time:

The Spinalis has a more intense marbling, and, thus, much more flavor and tenderness. If you are so bold, the next time you order a Rib Eye at a steakhouse, ask for an anterior “chuck side” cut that has more of this fantastic Spinalis muscle.

Preparation: There are a ton of ways to prepare a rib steak. The most comon forms are searing in a pan, grilling, or broiling. Another common method of preparing this kind of meat is roasting. A “standing rib roast” is a section of Rib Eye steaks that has not yet been portioned into individual steaks.

When this rack of ribs is roasted slow and low to a pink medium rare, the end product is called Prime Rib.

It then gets sliced out into portions for individual consumption. This is a mammoth cut that we got from Burger & Barrel:

I know what you’re wondering, and the answer is Yes: Prime Rib and Rib Eye steak are the same exact thing. They are just prepared differently, using different cooking methods.

Cheaper cuts of rib steaks are actually the most common type of beef found in Philly Cheesesteaks as well. The meat is cut super thin and then cooked on a flat top with cheese, onions and other toppings, then shoved into long sandwich bread (incase you’re an asshole who has no fucking clue was a cheesesteak is).

Side Bar: is a Philly Cheesesteak better than a Cheeseburger? I think so… Man… Now I’m hungry for both…

Flavor: This steak has a high fat content, and that makes it very important to have a quality cut of beef, or an aged cut of beef. In high quality and aged cuts, this fat will render out or melt away much easier during the cooking process. This will impart a tremendous amount of flavor into the steak, and it will leave the remaining flesh with a very tender and soft texture. Don’t be afraid of the fat. Fat is not the same as gristle. Fat is good. Fat is your friend. Any good butcher will get the gristle off and leave the good fat behind. And when that good fat is REALLY good, it’s like having a delicious beef jelly with each bite of steak.

As discussed above, the Rib Eye is really like having two steaks in one (The small Spinalis or fat cap, and the larger Longissimus eye). The Spinalis is soft, tender, has lots of fat flavor and sometimes develops a crisp during cooking. The eye is more dense, but still well marbled so that it retains intense flavor. The eye is more uniform than the Spinalis. So: two steaks in one, kind of like the Porterhouse. Plus, there’s a nice, meaty beef spare rib to gnaw on at the end, if you order a bone-in chop.

Since there is generally more fat and marbling in this cut across its entirety, you will get better flavors than with the tenderloin or Strip, in my opinion. Clearly, high fat content is not for everyone. If you want to avoid fats in your diet, then go with the tenderloin. I actually really enjoy the flavor of fat. Fat, now, is sometimes referred to as the sixth flavor sensation. There were always four: (1) savory, (2) sweet, (3) bitter and (4) sour. “Umami” claims to be the fifth, and is meant to encompass the earthy, funky, fermented flavor sensations that you experience with mushrooms, truffles, aged beef and blue cheese. I just dislike the word “umami,” so I use “earthy” instead. The sixth is “fat,” apparently, as decreed by various food people who get paid to sit around and do these things. I’m not sure how it works, but I seem to be able to recognize a distinct sensation on my tastebuds, along with a buttery flavor and slippery feel, whenever I eat shit like pork bone ramen or a Rib Eye steak. Maybe there’s something to it?

Anyway, I hope this was an informative and educational post for you meat minions out there. Knowing this shit, I think, is very important.